Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years—Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times by Elizabeth Wayland Barber sat, to my shame, on my bookshelf for about 20 years. I was interested enough to buy it, interested enough to keep it through uncounted moves and book purges, but never interested enough to read it. I simply had no interest in textiles, and well, women’s work. Women in the ancient world, yes. Women doing domestic things, no.

No interest, that is, until I started doing “domestic” things myself. A friend of mine recently had her first solo show, and I had my first real introduction to the world of art quilts. I had already started making first sock creatures and then peculiar dolls, so I had graduated from just hand stitching and had already bought my first sewing machine. So, throwing all caution to the wind, I set out to learn how to quilt from books and a quilting sister. I was finally caught and captured by those very domestic things I had so studiously avoided my entire life—women’s work. The next time I saw Barber’s book sitting neglected for 20 years on its shelf, I picked it up and have not looked back.

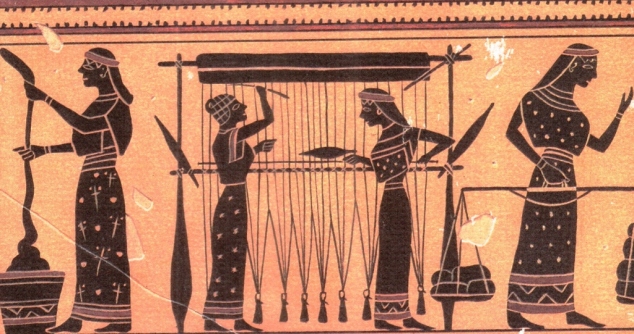

The book is surprisingly readable for a work based so firmly in academic research. Perhaps that’s because it is also just as firmly based in the author’s personal experience with the subject matter. She spins, she weaves, she sews. The introduction opens with Barber warping a loom with her sister in an account of her attempt to weave a recreation of an ancient textile: “We were weaving a thread-for-thread replica of a piece of plaid cloth lost in a salt mine in the Austrian Alps some three thousand years ago.” She is an expert weaver and an archeologist.

What’s most refreshing is that she concentrates on fact, not fiction, rarely falling back on mythology and treating it only anthropologically. She uses literature only to illustrate what has already been proven through archaeology. She uses data, obscure and hard to find on the subject, but that’s what makes the book so revolutionary. In her own words from the preface, “Perhaps the most important thing that has been omitted from this book, however, is fiction. … No evidence means no real knowledge.”

The book spans from the upper paleolithic to classical Greece, from Sumer to Egypt to Crete and many other points in Europe. We learn not only about women in the ancient (and prehistoric) world, but also about how textiles were produced, from gathering the wool to spinning and dying to weaving, uses, and fashions. The final chapter, a postscript, discusses her methods and “finding the invisible.”

This book truly fills a gaping hole in ancient history, not only recreating the role of women in society, but painting a vivid picture of the lives of individual women. In all my years studying classics, as many times as I came across women of the ancient world spinning and weaving, I never really knew what that meant (other than making cloth), could never really conjure more than a vague impression. Now I know. I’ve even spun with a drop spindle.

I’d love to get my hands on her previous (and likely more technical) work, Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in Europe and the Near East with Special Reference to the Aegean.